Peri-Menopause / Menopause

The Beginning

We are born with a set amount of eggs. Egg production in a female begins before she is even born. As a female fetus develops in her mother’s womb, her eggs (also called oocytes) are produced by the ovaries and stored in follicles within the ovary. Each woman is born with between 500,000 and 2 million eggs in her ovaries, but the number declines steadily from that point forward. For the average woman, only 300,000 eggs will remain by the time she reaches puberty.(43)

Though eggs are in large supply early in a female’s life, they are immature, and most will not reach full maturity because of a process called follicular atresia. Follicular atresia is a natural process wherein roughly 1,000 eggs are absorbed back into the body on a monthly basis. This process ensures that only the healthiest follicles with the best potential for successful fertilization are prepared for growth and maturation. From puberty to the onset of menopause, only about 300 to 500 eggs will reach full maturity.(43)

Then What Happens?

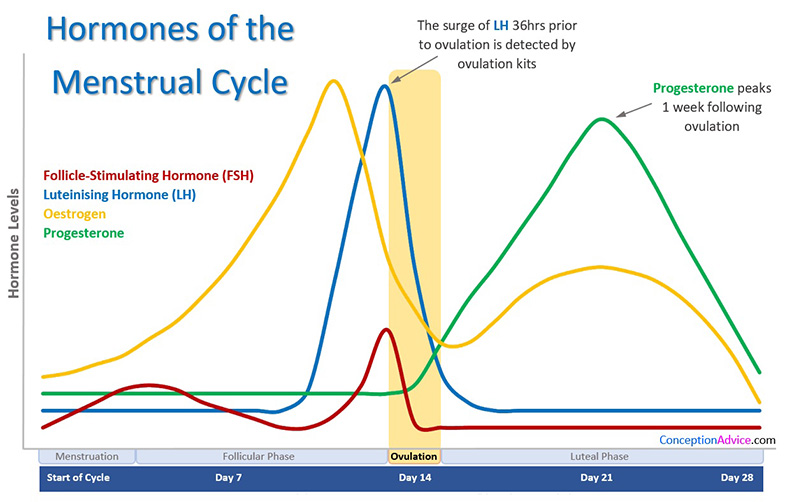

As a woman reaches puberty her menstrual cycle starts, her estrogen levels rise for the first two weeks or so, peak around day 12 and then begin to decline around day 13. Then ovulation occurs, and her progesterone level begins to rise and peaks about day 21. If the woman becomes pregnant, her progesterone continues to climb throughout the pregnancy. If no pregnancy occurs after about three to five days, then progesterone levels begin to decrease, and the next menses begins around day 28 or so. This cycle goes on–with estrogen being dominant the first two weeks of the cycle and progesterone dominant the second two weeks–for three to four decades of a woman’s life.

What Is Perimenopause?

This is the stage in reproductive life commonly defined as commencing with the onset of menstrual irregularity and symptoms When the perimenopause shift occurs, the pituitary gland begins to say, “Enough of this!” and slowly starts to turn down the volume of these hormones. It can happen in any number of ways, all perfectly natural, until the hormonal levels drop to the point that the cycle no longer produces menstruation. The cycle is still happening; the hormone levels are just not high enough to create a lining of the uterus that needs to be shed each month.

This phase of a woman’s life is often unrecognized until hormonal changes become more and more obvious. You may start experiencing symptoms that seem not hormone related at all.

Maybe you start forgetting where you placed your keys, or forget why you walked into that room. Or maybe you notice your hair and skin are not as vibrant as usual. Maybe sleep is becoming more disruptive and moodiness is happening a little more frequent than usual. These are just a few of the tell tale signs that your body is in the perimenopause phase.

In the early follicular phase (days 1-12 of the menstrual cycle) Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) levels in women who report menstrual irregularity fluctuate markedly. Anovulatory cycles occur at increased frequency in the last 30 months before the final menses (or menopause).

There is no specific endocrine marker of the early or late transition, making measurements of FSH or estradiol (E2) unreliable in attempting to stage an individual with regard to where they are in approaching menopause.(1-4) This is the time when females begin to have anovulatory cycles. This means that although a period is still occurring, this does not mean that we are ovulating every cycle. When we do not ovulate we do not produce the follicular changes needed to make the corpus luteum and produce progesterone. These hormonal changes are starting to occur earlier and earlier starting even as young as 35 with the average occurring between 40-50.(12)

Symptoms can start even before irregular cycles begin. At this stage of life the symptoms can be mild to severe. They can include changes in sleep, heart palpitations, brain fog, forgetfulness, feeling tired all the time, no motivation, low libido, dyspareunia, urinary incontinence, vaginal dryness including pain and itching, weight gain, metabolic changes, hair loss, dry eyes, joint aches, body aches, hot flashes, night sweats, migraine headaches, depression, anxiety, increased allergies and sinus infections, just to name a few.(4)(13-42)

What is Menopause?

Menopause is the cessation of a period and no viable eggs in the ovaries. Genetic factors may affect the age at which menopause is established.(2) Vasomotor symptoms are among the most common symptoms and their frequency, duration, and intensity vary. The data suggests that women who experience vasomotor symptoms are more likely to develop depressive disorders, mood and sleep disturbances, neuroticism, anxiety, decreased cognitive function and stress. The median age of menopause is 51.25 years.(1) Menopause may occur even earlier in females who have never been pregnant, in smokers, surgical oopherectomy, chemotherapy, or radiation to the pelvic area.(3)

What is the Risk of Menopause?

Adverse health outcomes and diseases like cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis may affect women later after the establishment of menopause. CVD is the main cause of death globally in both sexes. Ischemic strokes seem to cause more severe disabilities to women after menopause than men. The risk for vascular cerebral disease is almost doubled within the first decade since menopause. Post menopausal osteoporosis is estimated to affect 22 million women in Europe and has led to 3.5 million osteoporotic fractures. Fractures are correlated with increased morbidity and mortality and osteoporosis affects more than 10 million people in the United States. (8)

Physiologic Restoration™

Hormone therapy therefore has been considered as the most effective treatment for these symptoms (14). If a woman experiences symptoms of hormone deficiency, the reason to start hormone therapy may be not only to manage symptoms but also to maintain bone density and reduce the cardiovascular and neurocognitive effects of estrogen deficiency. The aim of hormone therapy is the protection against the negative effects of hormone deficiency. Physiological Restoration is replacing hormones to normal physiologic levels to avoid these declines. Mimicking the ovulatory cycle of a young female by using bioidentical transdermal estradiol and progesterone cream in doses that replace hormone levels to what is physiologically normal, like when they were young, not only is effective in relieving the symptoms of menopause, but may also be effective in preventing the health outcomes and diseases that occur after menopause.

1.Kaczmarek M. The timing of natural menopause in Poland and associated factors. Maturitas. 2007;57:139–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2.Laven JS. Genetics of Early and Normal Menopause. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3.Edwards H, Duchesne A, Au AS, Einstein G. The many menopauses: searching the cognitive research literature for menopause types. Menopause. 2019;26:45–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4.Portman DJ, Gass ML. Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel et al. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5.Lisabeth LD, Beiser AS, Brown DL, et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of ischemic stroke: the Framingham heart study. Stroke. 2009;40:1044–1049. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6.Lisabeth L, Bushnell C. Stroke risk in women: the role of menopause and hormone therapy. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:82–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7.Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M, et al. Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA) Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8.Lewiecki EM, Leader D, Weiss R, Williams SA. Challenges in osteoporosis awareness and management: results from a survey of US postmenopausal women. J Drug Assess. 2019;8:25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD007146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10.Ayo-Yusuf OA, Olutola BG. Epidemiological association between osteoporosis and combined smoking and use of snuff among South African women. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:174–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12.Miro F, Parker SW, Aspinall LJ, et al. Sequential classification of endocrine stages during reproductive aging in women: the FREEDOM study. Menopause. 2005;12:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13.Shadyab AH, Macera CA, Shaffer RA, et al. Ages at menarche and menopause and reproductive lifespan as predictors of exceptional longevity in women: the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2017;24:35–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14.Muka T, Oliver-Williams C, Colpani V, et al. Association of Vasomotor and Other Menopausal Symptoms with Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15.Faubion SS, Kuhle CL, Shuster LT, Rocca WA. Long-term health consequences of premature or early menopause and considerations for management. Climacteric. 2015;18:483–491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16.Archer DF, Sturdee DW, Baber R, et al. Menopausal hot flushes and night sweats: where are we now? Climacteric. 2011;14:515–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17.Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, et al. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2003;10:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18.Kravitz HM, Avery E, Sowers M, et al. Relationships between menopausal and mood symptoms and EEG sleep measures in a multi-ethnic sample of middle-aged women: the SWAN sleep study. Sleep. 2011;34:1221–1232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19.Hall MH, Okun ML, Sowers M, et al. Sleep is associated with the metabolic syndrome in a multi-ethnic cohort of midlife women: the SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep. 2012;35:783–790. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20.Donati Sarti C, Graziottin A, Mincigrucci M, et al. Correlates of sexual functioning in Italian menopausal women. Climacteric. 2010;13:447–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21.Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2133–2142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22.Campbell KE, Dennerstein L, Finch S, Szoeke CE. Impact of menopausal status on negative mood and depressive symptoms in a longitudinal sample spanning 20 years. Menopause. 2017;24:490–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL, et al. Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) J Affect Disord. 2007;103:267–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24.Soares CN. Mood disorders in midlife women: understanding the critical window and its clinical implications. Menopause. 2014;21:198–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25.Worsley R, Bell R, Kulkarni J, Davis SR. The association between vasomotor symptoms and depression during perimenopause: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2014;77:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26.Natari RB, Clavarino AM, McGuire TM, et al. The bidirectional relationship between vasomotor symptoms and depression across the menopausal transition: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Menopause. 2018;25:109–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27.de Kruif M, Spijker AT, Molendijk ML. Depression during the perimenopause: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:174–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28.Reed SD, Ludman EJ, Newton KM, et al. Depressive symptoms and menopausal burden in the midlife. Maturitas. 2009;62:306–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29.Vivian-Taylor J, Hickey M. Menopause and depression: is there a link? Maturitas. 2014;79:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30.Vousoura E, Spyropoulou AC, Koundi KL, et al. Vasomotor and depression symptoms may be associated with different sleep disturbance patterns in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22:1053–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31.Jones HJ, Zak R, Lee KA. Sleep Disturbances in Midlife Women at the Cusp of the Menopausal Transition. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14:1127–1133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32.Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Relationship between changes in vasomotor symptoms and changes in menopause-specific quality of life and sleep parameters. Menopause. 2016;23:1060–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33.Vincent AJ, Ranasinha S, Sayakhot P, et al. Sleep difficulty mediates effects of vasomotor symptoms on mood in younger breast cancer survivors. Climacteric. 2014;17:598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34.Kravitz HM, Zheng H, Bromberger JT, et al. An actigraphy study of sleep and pain in midlife women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Sleep Study. Menopause. 2015;22:710–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35.Ghorbani M, Azhari S, Esmaily HA, Ghanbari Hashemabadi BA. Investigation of the relationship between personality characteristics and vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21:441–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36.Ormel J, Jeronimus BF, Kotov R, et al. Neuroticism and common mental disorders: meaning and utility of a complex relationship. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:686–697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37.Bal MD, Sahin NH. The effects of personality traits on quality of life. Menopause. 2011;18:1309–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38.Lin MF, Ko HC, Wu JY, Chang FM. The impact of extroversion or menopause status on depressive symptoms among climacteric women in Taiwan: neuroticism as moderator or mediator? Menopause. 2008;15:138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39.Chou CH, Ko HC, Wu JY, et al. Effect of previous diagnoses of depression, menopause status, vasomotor symptoms, and neuroticism on depressive symptoms among climacteric women: A 30-month follow-up. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:385–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40.Constantine GD, Graham S, Clerinx C, et al. Behaviours and attitudes influencing treatment decisions for menopausal symptoms in five European countries. Post Reprod Health. 2016;22:112–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41.Structural and functional brain changes in perimenopausal women who are susceptible to migraine: a study protocol of multi-modal MRI trial. Hu B et al. BMC Med Imaging. (2018)

42.Migraine in perimenopausal women. Allais G et al. Neurol Sci. (2015)

43.Immunoregulation of follicular renewal, selection, POF, and menopause in vivo, vs. neo-oogenesis in vitro, POF and ovarian infertility treatment, and a clinical trial Antonin Bukovsky1 and Michael R Caudle2